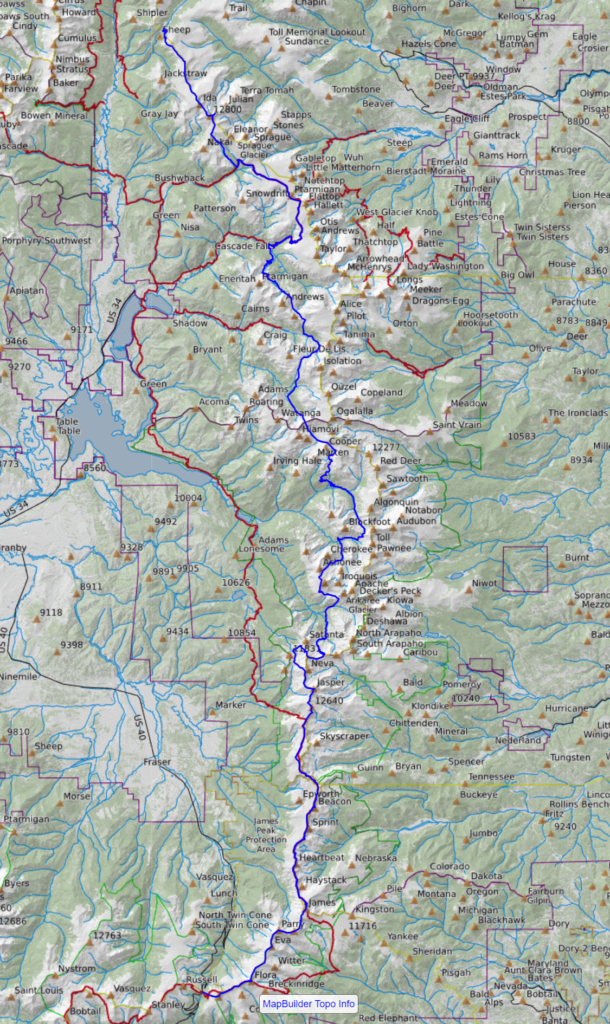

In September of 2023, I completed the Pfiffner Traverse. The Pfiffner is a high route that follows the Continental Divide along the crest of Colorado’s Front Range between Milner Pass to the north and Berthoud Pass to the south. This post provides a brief overview of the route as well as reflections from each day, a gear list, meal plan, and a few photos.

Pfiffner Traverse Overview

The primary route as outlined in Andrew’s guide (details below) is about 75 miles long with 28,000′ of elevation gain. It’s comprised of sections of established trail, including portions of the Continental Divide Trail (CDT), as well as sections of cross country travel, which make up about 40% of the total mileage. The technical level of the terrain is mostly Class 1-2 with occasional sections of Class 3 travel. I hiked solo and completed the route in a little less than four days.

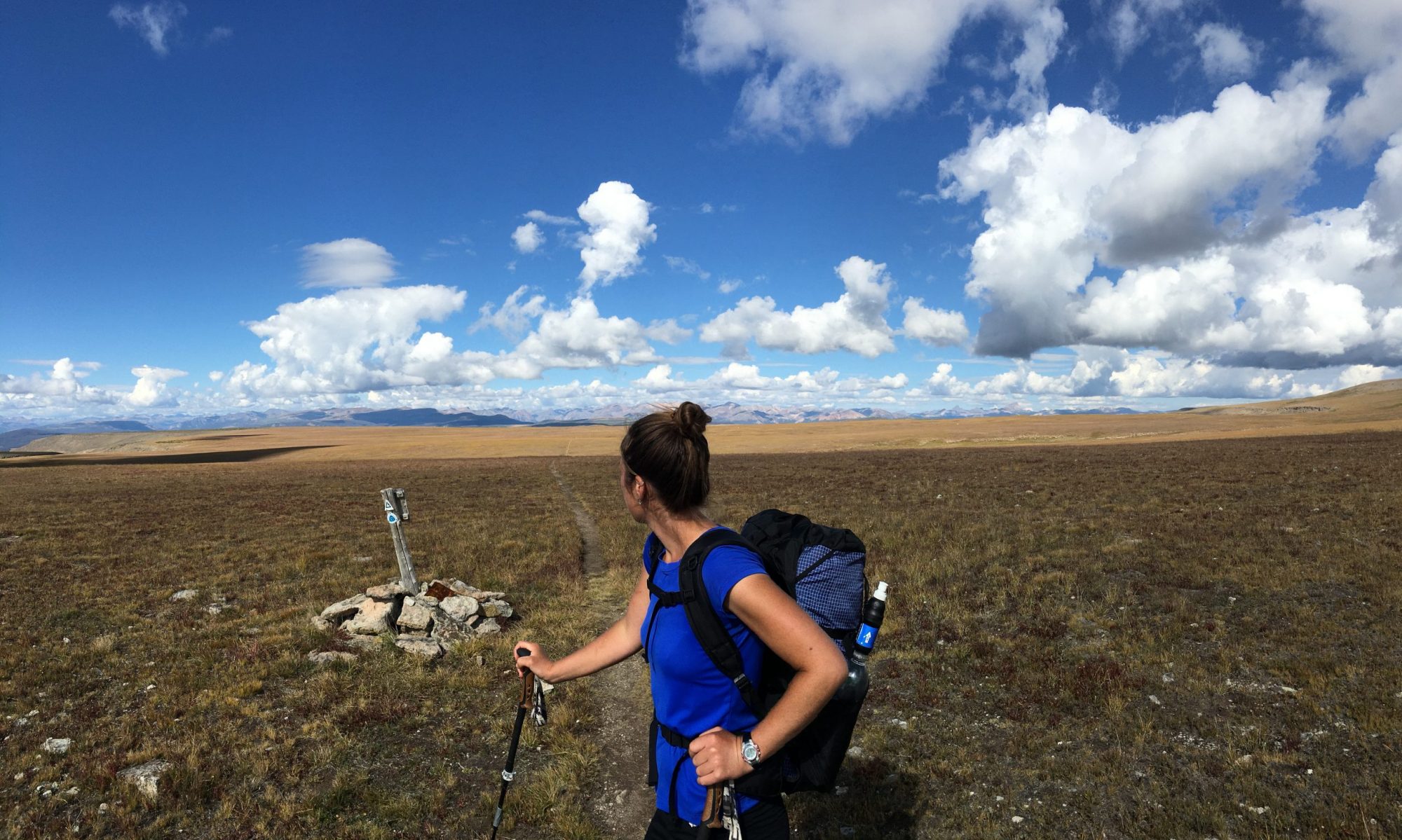

The route drops below 10,000 feet only twice. It’s an engaging line with ridge walking and expansive views in the northern section, pass-and-basin terrain throughout the middle, and caps off (for southbounders) with a nine mile ridge walk that traverses five 13ers before dropping down to Berthoud.

While it can be hiked in either direction, I chose to hike southbound due to logistical reasons. Starting at Milner Pass allowed me to plan my RMNP campsite reservation more accurately, pick up my backcountry permit on the way to the start of my hike, and to more easily arrange my transportation (leaving a car at Berthoud Pass and being dropped off at Milner).

My goals were to:

- Move light and fast, testing my alpine fitness

- Enjoy solo time outdoors in beautiful and challenging terrain

- Visit seldom seen areas of Arapaho NF and RMNP

- Spend a few nights sleeping outside during one of Colorado’s dreamiest months

- Get out for one last multi-night high country trip before before guiding in West Virginia in early October, after which access to the alpine becomes hit or miss

History

I find the history of this route fascinating. Karl Pfiffner was a Boulder-based mountaineer in the 50’s. He died in an avalanche on La Plata Peak when he was just 25. He was a friend and climbing partner of well-known (if you’re a Colorado outdoors-person) mountaineer author Gerry Roach.

In Gerry’s book Transcendent Summits, he writes “One of the projects that Karl had talked about doing was traversing the Continental Divide between the Arapaho Peaks and Longs, and he was making plans to do this traverse in the summer of ‘60. I resolved that I would someday do the traverse in his memory. Indeed, decades later, an extended version of this traverse still carries Karl’s name, and the next generations would do well to remember the namesake of this route.” Roach hiked a version of the route in 1987. You can read more about the history of the route on Andrew’s site.

Preparation & Resources

This comprehensive guide contains a mapset, datasheets, permit information, and route description among other resources. I found it particularly helpful as I didn’t have much time to plan. As with any outdoor endeavor you still need the fitness and appropriate skill sets to complete the route, but you’re interested in this route, there’s no better place to start.

- NWS point forecast

In the week leading up to the trip, I regularly checked forecasts from locations at varying elevations and locations along the route, such as Milner Pass, Thunderbolt Peak, and Berthoud Pass. This informed last minute gear decisions.

- CalTopo

I primarily used this mapping software to sketch a digital route as well as alternates based on descriptions in the guide. This was meant to accompany my detailed printed maps if needed. I also used CalTopo’s sentinel layer to check snow conditions in the NE Gully.

- Trip reports

I looked for recent trip reports to assess the amount of snow in the NE Gully to ascertain whether I needed an ice axe and/or spikes. I found one or two reports from 2023, though only one was even somewhat helpful since it was from within a month of my start date.

- Timeline

Having completed the Sangre de Cristo Traverse a month earlier, I was in decent alpine shape and I wanted to use this trip as an opportunity to push myself. I determined my timeline based on my daily vertical limit, which was around 7000-8000 feet per day. Based on my experience in the Sangres, I was fairly confident I could sustain that pace for the duration of this route, which would equate to roughly four days (28,000 feet of total vertical divided by 7,000 feet per day).

Challenges

- Weather. The route spends several continuous miles above treeline at various points. As most hikers familiar with mountain travel are aware, weather can move in abruptly. There are lower elevation alternates that can be taken for most sections of the route. I was aware of these, and as I describe below, still found myself outrunning an afternoon storm on day one.

- Elevation. Since I live at 7,000’ and hiked this route after a summer spent backpacking above 10,000’, I didn’t find this to be an issue. But it’s an important planning consideration for anyone coming from sea level.

- Vertical per mile. With 760 feet of climbing or descending per mile, the vertical change is steady throughout. Good to be aware of this and plan your itinerary accordingly.

Highlights

- Hiking the first couple of miles with my mom and brother

- Engaging route finding and following bits of elk trail

- Golden aspens, crimson ground cover, and frosty morning vegetation

- Elk bugling in the valleys

- Long nights, crisp mornings

- Solo mountain time

- My moose encounter (details below)

- Hiking through pristine alpine lake basins in lesser visited parts of RMNP and Arapaho NF

- Seeing very few people despite being less than two hours from Denver

Pfiffner Traverse: Day by Day

DAY 1

- Miles: 19

- Vertical gain: 5300’

After coffee, an elk sausage frittata, and a large side of fried potatoes, which I dutifully finish reasoning that I’ll be grateful for the calories later, my mom, brother, and I depart Grand Lake, and head for the Kawuneeche Visitor Center. After a brief chat with the ranger, I have my backcountry permit in hand and we’re winding our way up towards Milner Pass.

The plan was for my family, visiting from Ohio, to hike with me for an hour or so before heading out through Estes Park and onward to DIA. Though they’ve always been supportive of my hiking habit, they’ve never been physically present for the beginning or end of one of my trips. We didn’t backpack together when I was young, but we spent a lot of time outdoors – spring morel hunting, summer car camping, winter skiing, autumn glassing for deer. They’re the reason I feel so at home outdoors and it felt special to have them here.

Our 10:30am start is later than ideal, but I decide that it’s acceptable because the chance of precipitation is only 30%, the mileage to my RMNP campsite isn’t far, I have low elevation alternates if needed, and ultimately, the time with my family is priceless. We enjoy a few miles together, and too soon, it’s time for them to turn back. After hugs and well wishes, I head up the trail solo, a heaviness in my heart.

Gradually ascending to the ridgeline with gorgeous views of the surrounding ranges, the mid-September air is crisp and perfect. I’m watching the weather that’s building to the east. Passing a few parties of hikers, I depart the trail and push to get over Mt Ida as the wind picks up. The weather blows in fast and graupel pelts my face as I crest Ida and begin scrambling down the south side to the relative safety of the saddle. With my attention fully focused on the sky, I stumble on some talus, and full send. I stand to find a large bloody scrape on my left thigh and a sore right knee. Okay, off to a good start.

Sheltering behind a boulder, I throw on layers, inhale a snack, and check my map for a lower elevation alternate. At the Chief Cheley saddle, I make the conservative call and head down towards a low route. About 200 feet down, the graupel stops and it looks like the storm has blown over. Not wanting to give up my hard-earned elevation gain, I stupidly begin to side hill on talus around Cheley. Upon becoming sufficiently annoyed with this plan, I crawl up class 3 terrain on the east face to regain the ridge where the easier walking is found.

I enjoy an hour of sun before the next squall hits. The snow begins as I descend past Haynach Lakes and fortunately, already under tree cover. I join the CDT and power up through a burn area in the Tonahatu Creek drainage, feeling strong. Back above treeline, I spot more weather to the north. It’s slowly moving my way. Knowing I’m exposed for the next five miles, I pick up the pace. Anxiety builds as the storm inches closer.

Just as I hit the south side of Ptarmigan Pass, the snowfall begins again. Thankfully, I’m beginning my descent towards North Inlet and tonight’s campsite. Within moments, the entire sky is a deep bluish purple and it’s clear this squall is more serious. A loud clap of thunder rattles above. I race toward treeline and the descent into Hallett Creek as the snow pummels my bare skin. Around 10,000 feet, the snow turns to rain, and it’s not long before I’m soaked and cold and my hands are going numb. With the fading daylight, there’s no chance of drying out as I descend into the trees. In an act of mercy from the universe, the rain finally clears and golden beams of the day’s last light shoot through the pines, diffusing the most celestial light throughout the misty valley.

Down down down, I finally reach camp around 6:45. Wet and cold, I fumble to set up my shelter with my barely functioning hands, the task taking three times longer than normal. I peel off wet layers and get something dry on, the adrenaline slowly clearing out and the exhaustion settling in. Gather water, crawl into my bag, and get some hot food going. Finally able to relax, I study my maps, hoping for a better weather day tomorrow.

DAY 2

- Miles: 19

- Vertical gain: 7600’

Sleep is intermittent as I have weird dreams and vague worries about putting on wet clothes and walking through more storms. I awaken groggily to the sound of my alarm at 5:33. Frost covers my tent and I can see my breath. Lighting my stove for coffee, I decide I’m not walking until it’s light. Even though I know about the potential time sucks I could encounter (difficult off trail travel, navigational errors, and weather), I’m dragging my feet. Know better, I tell myself that even if I leave by 7, I still have 12 hours of usable daylight. I text Troy for an updated forecast and eat slowly.

Having consumed my coffee and breakfast and with no other ways to procrastinate, I crawl out and pack up my frozen, wet shelter. Even with gloves on, my hands become numb. Ascending through the trees on snow-dusted trail towards Lake Nokoni, it’s cold, but beautiful as birds chirp and the sky lightens. I’m grateful for the elevation gain as my working muscles generate body heat.

Lakes Nokoni and Nanita are the most picturesque alpine lakes and I wish I had time to linger. Orange and yellow leaves lay atop a crimson ground cover. I remember that it’s the 21st. Happy first day of autumn, I say aloud. At the saddle above UN Lake 10584, I’m finally in full sun, and I stop for a snack. It’s chilly and the sun feels wonderful. I get a message from Troy that the radar looks better for today. I hope it’s accurate.

With more optimism in my step, I push on, up over a pass, down into a basin, up over a pass, down into a basin, and repeat for the remainder of the day. Departing Beak Pass, I make my way down through forest and over blow downs to East Inlet, where I pick up good use trail around the lakes. On the south side of Isolation Peak Pass, I cruise bits of elk trail through the remote and aptly named Paradise Park, and exit RMNP via Paradise Pass. I skirt along the east short of Upper Lake, stopping to refill a bottle. Resting on a rock in the sun, I eye Cooper Peak Pass, which looms 1100’ above me. Climbing up the steep tundra, then talus, I reflect on another summer coming to a close and what am amazing one it was. Soon, I’m up and over, descending the talus towards Island Lake.

Around 4pm, a storm moves through the next valley to my east. Flashing back to yesterday, I get a bit nervous, but it passes by without trouble. I pick up trail near Gourd Lake and make fast miles until shortly before dark when I hit the junction of Buchanan and Thunderbolt Creeks, where I begin to look for camp.

I’m disappointed to stop 1.5 miles and 1,000’ short of my goal for the day, but due to the late start and slow off trail travel, I’m not surprised. I find a protected spot in a pine grove just north of a chilly-looking meadow. I’m grateful to be warm and dry as I set up my tent with fully functioning hands. I cook dinner as the last of the day’s light drips from the sky. Just as I start to eat, I’m startled by a loud rustling very close to my tent. I fumble for my headlamp and scan the pine grove. The beam catches a set of glowing deer eyes staring back at me just 10 feet away.

I get a message from Troy informing me that tomorrow’s forecast looks clear though I may get a storm tonight. And just as I read it, a clap of thunder booms overhead and rain starts to fall. Grateful to be in my cozy nest, I study tomorrow’s route. It will be another long day with the most challenging terrain encountered thus far. I remind myself that I planned it this way as I drift off to the sound rain on my tarp.

DAY 3

- Miles: 14

- Vertical gain: 7500’

After a night of decent sleep, I’m hiking by 6:30 and there’s just enough light to not need a headlamp. I walk along the timber at the edge of a meadow through frost-covered grass, noticing the temperature difference between my campsite and the frigid meadow. Shortly thereafter, as I exit the meadow to the south, I’m startled by loud grunting and brush thrashing sounds coming from behind me.

I whip around to see a bull moose charging straight towards me through the meadow. It quickly becomes clear that it’s not veering off its course. Frantically, I search for an escape. I know I can’t outrun it so I break through a mess of dead limbs and force my way up the trunk of a blowdown that’s wedged against a standing tree. It’s not much, but this at least gets me 7-8 feet off the ground.

Just as I’m positioned in the tree, the moose bursts through the edge of the timber 30 feet away and stops to look around. I make a loud noise foolishly thinking I’ll scare it off. Looking in my direction, it strides fifteen paces closer, snout uplifted, sniffing my scent on the air. Suddenly I remember that moose have very bad eyesight and I stand as still as I possibly can. After a few minutes of staring straight at me, it turns its massive head, thrashes some brambles with its antlers, and begins to wander up-valley in the same direction I’m headed.

Realizing that I’ve been holding my breath, I let out a long exhale and watch until it’s out of sight, allowing my sewing machine leg and heart rate to return to baseline. I climb down the tree, relocate the elk trail I’d been following and keep moving, hoping that was the last I’d seen of him.

Alas, not ten minutes later, I cross an avalanche slide clearing and spot the same moose on the opposite side of the creek. Darn! I step behind a tree, giving him more time to wander out of sight on the opposite side of the narrowing valley before I tip toe my way across the talus. Hoping to get ahead of him, I pass through more timber and into another clearing. I vigilantly scan the timberline and I spot him a few hundred yards away, still across the creek, looking straight at me.

Now in another avalanche path clearing, there’s nowhere left to hide, and the moose is slowly ambling in my direction. I hike uphill as fast as I can toward steep bluffs at the head of the valley, trying not to look like a threat. He continues to meander towards me and I keep moving as fast as I can, finally reaching the bluffs before he catches up to me. I climb onto the wooded grassy ledges next to a waterfall and look back. The moose stares for a few minutes before losing interest and turning back down valley. Thankful to be in relative safety and annoyed that this diversion has eaten up precious daylight, I charge up the drainage towards my immediate objective, Paiute Pass.

The pass is snow free, as expected this late in the season, and I go straight up and over with a short class 3 scramble. The descent is more straightforward than I expect with just a little deadfall to work through. Soon, I’m busting through the trees and onto the Pawnee Pass trail, startling some hikers. I smile, hop on the trail, and cruise west, excited for the chance to make up a little time. At the first junction, I begin my ascent towards Crater Lake and the most challenging feature of the route, the Northeast gully of Lone Eagle cirque.

I make quick work of the trail up to the campground and head towards campsite 12 from which I need to begin my ascent. I pass sites 10 and 11 on decent trail which then splits into several use trails. I pursue the most well-trod one and it leads me to the lake and some steep bluffs. I return to sites 10 and 11, and pursue another, and it leads uphill to a stealth site on a bench. Impatient, I return to the lake and skirt along some ledges between granite bluffs, making my way along the edge of the lake while feeling fairly sure I’m off route.

Revisiting my maps, indeed I’ve gone too far around the lake, but I can see my next objective so I decide to push straight uphill through thick brush. It’s not graceful, but it gets the job done. I continue to grind up the steep terrain until finally, I’m about a hundred feet below the top of the NE gully and my exit from the cirque. There’s one large patch of snow in the shaded north side.

Having recently melted out, the footing is steep, loose, and chossy. I start up the most stable talus, which ascends toward the snow patch where I plan to cross beneath it and climb the right wall on sandy but snow-free talus. I begin my crossover, and the footing is extremely loose and I begin to slide. Changing my plan, I reverse and begin to climb the rock to the left of the snowfield. It looks like I can cross over above it. The pitch steepens as I climb and I’m making class 4 moves on less-than-ideal footing that I don’t want to have to reverse. Don’t go up what you can’t come down, I remind myself.

Above the snowfield, my passage straight up and over is blocked by steep, sandy slabs with no holds. Crossing over to the east requires a few steps on steep, loose ice sand, also with no holds. Downclimbing would be doable but risky. I look at the runout in the event of an unarrested fall. I select the least awful option and mentally rehearse my moves across the steep, loose gully. I complete my sequence but not without a tenuous foot hold giving way beneath my left foot mid-way across, causing me to slide on my side a few feet before I’m stopped at a ledge.

I stand up, blood droplets forming up the length of my left leg and hand. After a quick inspection to confirm I’m fine, I hop the rest of the way across and climb the remainder of the talus and scree up to the saddle. I sit down, regroup for a few minutes, and carry on. The route finding for the descent into Wheeler Basin and Coyote Park is enjoyable, requiring me to stay engaged and focused.

My intended campsite was Columbine Lake, but with the sun setting behind Satanta Peak and facing an icy wind as I crest Arapaho Pass around 6:45, I pull out my maps to evaluate the options. Rather than hike a ridgeline at 12,000’ in the dark with winds increasing and temps dropping, I make the decision to drop down to the south side of Arapaho Pass and find camp in a protected grove near a creek. From there I’ll have options for reconnecting with the primary route in the morning.

Troy messages me that tomorrow is expected to be clear, but very windy with 45 mph gusts. Great, I’ll be on an exposed ridgeline for most of the day. I’ll take it though: wind I can handle. At least it’s not precip. I look over my maps, weigh my options for regaining the crest, and decide on a route with a decent amount of confidence that it’ll go.

Before drifting off to sleep, I glance up at the starry sky and waning crescent moon, and reflect on the day, from the moose encounter to the beauty of the terrain to the NE gully to the decision to reroute. I’m spent, both mentally and physically, in that gratifying way I’ve only been able to find by pushing myself in the backcountry. It’s been a jam-packed few days. I look forward to a solid finish tomorrow. Body, stay strong. Mountains, grant me safe passage.

DAY 4

- Miles: 24

- Vertical gain: 8,000’

Moving by 6:45, I admire the pink, blue, and purple sunrise lighting up the valley over the Front Range. I’m excited for my last day, which should be mostly on trail and straightforward, with wind, but no storms. It’s a big day, but I expect to be at my car by sunset, sleeping in my bed tonight.

My route works out, and despite a tired body, I make good progress. By 10am, I intersect the CDT near Devil’s Thumb, having seen a few hikers and hunters along the way. Golden aspens twinkle in the morning light, and I hear the eerie bugle of elk in the valleys below as I walk an old, unmaintained stock trail, the wind picking up the higher I climb. My alternate ends up being nearly identical in mileage and vertical to the primary route, but lacking in off-trail fun, remoteness, and solitude. If timing and daylight hadn’t been an issue, the guidebook route is the way to go.

Once on the CDT and bundled up for the wind, it’s time for some good ol’ mindless mile-crushing. After the previous three days, and despite the steady 20mph winds, this feels like just what I want. At Rollins Pass, I take my first real break of the day tucked in behind some boulders. I down some food and water, pop in headphones, and prepare for the final push: nine miles over five 13ers, all off trail on an exposed, windy ridge before my final descent into Berthoud Pass.

I crawl out from my boulder shelter, sky clear, wind howling, and begin pushing up the tundra and talus on the north side of James. I feel depleted from the previous days’ effort as I will my heavy legs through the steadily increasing wind. C’mon body, let’s do this. The terrain between James and Bancroft Peaks has some fun little scrambly bits that provide a nice distraction to the slog. I talus hop from Perry to Eva, and soon I’m facing my final steep climb up Flora. The shadows have already taken over the east side of the ridge to my left, and the cooling winds chill to the bone. Step step step. Just keep moving upward.

As the sun sinks low in the sky to the west, I top out on Flora. I did it. Just three miles downhill on trail to Berthoud. As I switchback down down down towards the headlights creeping along highway 40, I dream of dinner, a shower, and bed. I turn on my phone to text my family that I’ve made it. Finally, at 6:20, I’m at my car!

I collapse into the front seat, mentally and physically beat up, scrapes all over my body, relieved to be done. I head towards dinner in Silverthorne, and soon I’m sitting in the dark in my car inhaling Chipotle, tears flowing down my face from the pain of Tabasco on my sunburnt lips. Troy texts to see if I made it.

“I did!”

“Good. I was about to start driving towards Berthoud Pass if I didn’t hear from you soon.” We make plans for which 13ers we’ll climb the following day. Under a starry sky, I drive the windy roads toward Salida with a weary body and a full belly, feeling deep gratitude for a good trip and this amazing life.

Wow! What a hike–Congrats & thx for sharing (& your story of sharing trail w/that moose!)