I was recently interviewed for a project with a popular outdoor magazine about my favorite methods for purifying water, how to find water in the backcountry, how to stay on top of hydration, and the effects of dehydration. I ended up not moving forward with the project after seeing the contract, but the interview had already been done and we covered some important topics, so I wanted to recreate it for this post.

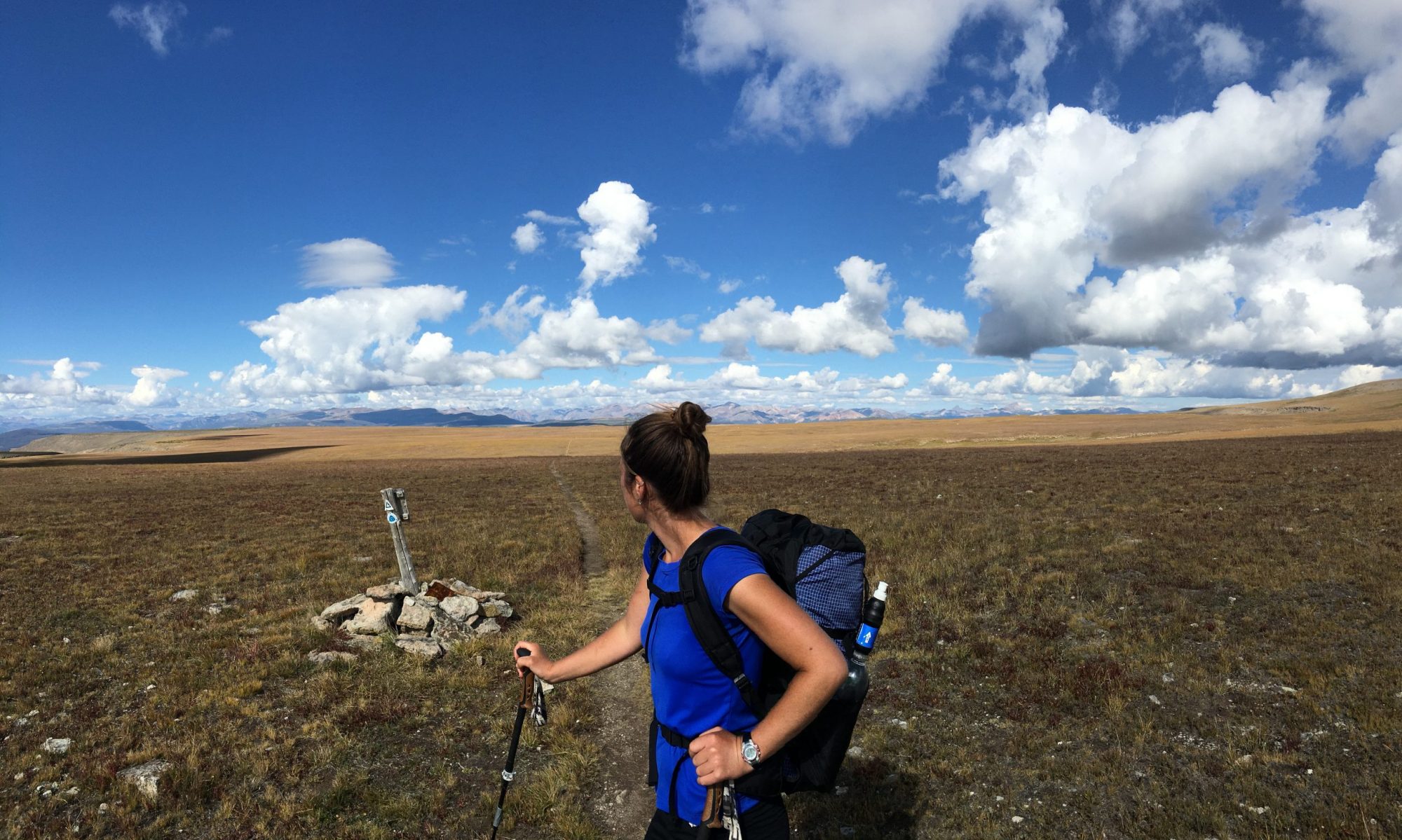

For context, this is based on my experience backpacking the Pacific Crest, Continental Divide, Oregon Desert, Colorado, and Great Basin Trails, in addition to dozens of shorter trips. I’m not a water expert, but I do have a lot of personal experience with this topic, and that’s what I’m sharing here.

Water is essential for survival and finding it and treating it can be a concern for many backpackers. Learning this information gets you one step closer to feeling more confident on your next backpacking trip.

How do you find water on a backpacking trip?

Above all, I believe that knowing how to read and interpret a topographic map is an invaluable backcountry skill. You can learn the basics by reading articles online or taking a course, and best of all, practicing in the field.

Before heading out for a trip, use a paper or digital map to locate water sources, such as lakes, rivers, creeks, etc. However, keep in mind that just seeing a blue line on the map is not enough. It’s important to think about when the map was created, how reliable the water source is, and whether it is likely to be flowing at the time of year you’ll be there. For example, sources are generally more likely to be flowing in the spring versus the fall. Satellite imagery, such as Google Earth and specific layers on mapping apps, such as the US Hydrography layer on Gaia GPS, can also be helpful for locating sources. Contacting locals and/or land managers can provide further insight into whether sources are flowing when you plan to go on your trip.

In addition to the above research, when you’re hiking a more established trail, such as the PCT, you can reference crowd-sourced water reports, such as sites like pctwater.com and on apps like the FarOut app (formerly Guthook). Be sure to note the date of any information you’re reading and take that into consideration.

How do you assess water quality in the backcountry?

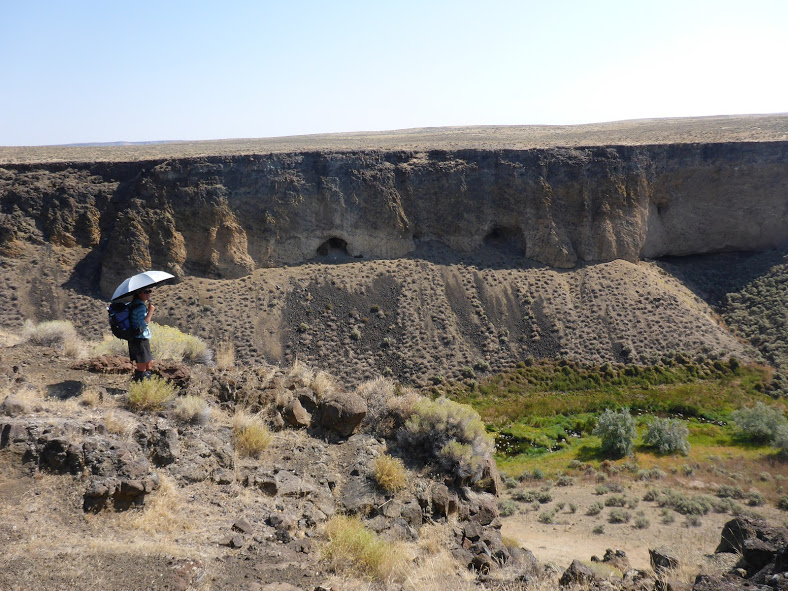

I’ve hiked in a lot of dry places, such as eastern Oregon, the Great Basin, the Mojave and other parts of Southern California, southern Utah, the Red Desert in Wyoming, and southern New Mexico. Water sources are often questionable and it’s not uncommon to need to collect water from cow tanks, potholes, and other less-than-ideal sources. That said, I always assess water quality, and choose the least disgusting source possible.

Some factors I use to assess water quality include:

- Considering how far I am to the source – the closer to the source I can collect, the better.

- Considering what’s upstream, such as livestock, wildlife, and other hikers.

- The turbidity of the water – the clearer the better since sediment can reduce the effectiveness of certain purification methods, such as UV and chemicals.

- Is there a chemical film and/or dead animals, such as cows, mice, or birds in the water? Dead animal water and chemical water is a no-go for me.

- Does the source smell bad?

What is your favorite method for treating water?

There are several methods for treating water, including boiling, chemical, filtration, and UV light. My personal method of choice is an inline squeeze filter, such as a Sawyer Squeeze, which is compatible with a variety of water containers including hard-sided bottles and collapsible pouches.

I also use chemical filtration, such as Aquamira (aka chlorine dioxide) drops or tablets when it’s below 15 degrees Fahrenheit.

If I’m drinking from a particularly gross source, I might use multiple methods, such as filtering through a bandana or shirt to remove sediment, then treating chemically, then filtering through an a water filter.

When selecting your filtration option, it’s valuable to know the likely water contaminants in the area you’re traveling and what your chosen treatment method is, and is not, effective against. For example, most filters don’t filter out viruses, though viruses aren’t that common of a contaminant in most backcountry water sources in the U.S.

What do you look for in a water filter?

When selecting a water filter, I look for one which removes bacteria, parasites, and most chemicals and microplastics. I also want something lightweight, ideally less than 4-5 ounces including the bottle or pouch. The higher the flow rate the better as the time really adds up when you’re filtering 4-6 liters per day for months on end. I also want something compact so it doesn’t take up much space in my pack, and I want something that’s durable and made from high quality material so that I don’t have to constantly replace it and I can avoid creating more waste that will go into a landfill.

How do you stay on top of hydration during long days in the backcountry? What is the effect of dehydration? How do you avoid overhydration?

Staying hydrated is important for optimal functioning of your mind and body. As little as 2% dehydration can have impacts on your performance, including increased fatigue, muscle cramping, and a decline in cognitive function. I make sure to balance my water intake with electrolytes, such as potassium, magnesium, and sodium to avoid hyponatremia.

To ensure I stay hydrated, I know where my water sources are and I make sure I carry enough water with me to get from one source to the next. That amount varies based on the temperature, sun exposure, wind, and intensity of the section, but generally I carry enough to drink about 1 liter per 5 miles. I carry more if my next source is questionable, especially on a route where I have no one hiking ahead of me to provide beta. In addition to carrying enough, I make sure to keep water in an easy to access location, such as my side pockets, so that I can drink on the go without needing to take off my pack.

I like the Katadyn beFree, a squeeze filter, weighs 3.5 oz with a 1 ltr bag. I also carry a 1 ltr platypus bag, weighs less than an ounce, to drink out of during the day-and add in my electrolytes. This fits nicely in a side pocket. I bring 3 ltr platypus, weighs barely over an ounce, to fill at the end of the day; or if a water sources are far apart.