I lean into the wind—a solid, invisible wall—forcing my body forward, toward the valley head. It takes the full weight of my body just to maintain balance. Next to me, I see Troy’s silhouette fighting the same impossible force, bracing against the whipping dust. The sky is gone, replaced by a churning, opaque fog of beige dust. Every inch of me is covered, yet the sand finds a way in. Beneath my buff, grit scours my teeth, and my eyes, burning behind sunglasses, water incessantly. All I hear is the constant rattle of thousands of grains of dust blasting the hood of my jacket. Two questions swirl in my head: What am I doing here? Why did I feel compelled to come here?

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s start from the beginning.

Route Overview & Intentions for Going

Iceland had been on my radar as a backpacking destination for a long while, and being on the cusp of my 40th birthday, I decided this year was the year to make it happen. I was drawn to the natural beauty, of course. I also wanted to experience what makes the culture and people unique, and to enjoy a multi-week backcountry trip with Troy. At least these were the logical-sounding reasons that I told myself and others when they asked.

To be honest though, I wasn’t sure exactly why I was going. I just knew that it was a destination that kept surfacing in my mind, and I was confident that at the end of the day, if I was spending two weeks moving through nature, wherever I was, it’d likely be worth it.

So, I set to planning and in August of 2025, Troy and I spent two weeks walking across Iceland, an island of rough, volcanic extremes that’s nestled in the North Atlantic a few degrees south of the Arctic Circle. It has a subpolar oceanic climate that creates famously unpredictable weather, with strong winds and frequent rain being common year-round. Our route covered roughly 340 miles and consisted of cross country travel, rugged 4×4 roads, and maintained trails. Walking surfaces included sand, volcanic rock, dirt, gravel, moss and grass.

It’s a desirable destination for many reasons, not the least of which is the unparalleled natural beauty. Known as the land of ice and fire, the landscape is shaped by ongoing volcanic, tectonic, and glacial activity. Traveling across the country meant an immersive tour of the powerful forces of ice and fire: massive glacially-fed rivers, expansive ice caps, and a variety of geothermal features including volcanoes, fumaroles, boiling mud pots, lake-filled craters, steaming rivers, and black sand beaches.

That wind would be our faithful companion throughout the journey, driving us mad in one moment and offering an opportunity to practice ultimate surrender the next; our response dictated by our current moods and capacity for discomfort. Of course, I’d known this was likely to be the case when I started my trip research eight months prior. But it’s always hard to imagine exactly how challenging something might be from the comfort of your desk, well-fed, in a temperature-controlled room. From there, the idea of hiking across Iceland sounded great.

Iceland day-by-day

Húsavík to Reykjahlíð

Shortly after 1pm on a drizzly gray afternoon, we set out east from Husavik, a town of about 2,500 inhabitants best known for its incredible whale watching. True to our natures, like we’re heading out for a walk up our local Tenderfoot Hill, we set off in silence. No fanfare, just walking.

While creating our route in the months prior, we quickly found that the options for crossing the island are many. Ultimately, our decision to start from Husaik, rather than the northernmost lighthouse of Hraunhafnartangi, was a logistical one. There’s no longer public transport to the lighthouse and our schedules didn’t allow for us to spend an unknown amount of time waiting for a hitch. Walking out of town was easiest and most efficient.

Loaded with 12 days of food, the shoulder straps of my pack dig into my shoulders and cause my iliac crest to go numb, but I barely notice as I’m so delighted to finally be walking after nearly 48 hours of travel and final preparations. Birch trees and lupine blooms line the path drawing me towards the first of hundreds of lakes to come. Half a dozen gulls dot the surface. As we climb above the shrubbery, I look back over my shoulder to see the town nestled into a small bay. Beyond is the ocean, an endless expanse of aqua blue beneath a low gray cloud. After months of planning and ironing out details, it’s liberating to finally be executing the plan. Nothing more to do except walk now.

The remainder of the afternoon is a blur, time muddled as we hike alongside a road, in a cloud. Fortunately, traffic is sparse and the miles go quickly. Road walking is never my preference, but as I gaze up at our off-trail high route option encased in cold rain and wind, I’m grateful to be down low. It’s day one and already I’ve worn all the layers I’m carrying. I feel justified for throwing in the extra mid layer and heavier rain gear.

Around 7pm, we find a protected spot behind a knoll to set up camp in a clearing of dwarf birch. I’m satisfied to have put in a solid day of walking despite our late start. We get a hot meal in us and, still jet-lagged, fall into a deep sleep soon afterwards.

The storm clears overnight and we awake to clear skies and sun. Our spirits are high and we pass the morning walking dirt paths eastward towards Vatnajökull national park. The old farmer’s roads are the most efficient walking here as they create a navigable route through a landscape full of deep fissures and mounds of lava rock that are covered in a dense layer of dwarf birth, crowberry, lichen, and moss.

The only life to break the volcanic stillness are the domesticated sheep. They roam the land and bring me joy. We unintentionally startle them from their burrows beneath overhung shrubbery, surprising both them and us. Baaaaaing, they scurry up the road and then we repeat the whole thing thirty minutes later when we come across them again. And again and again.

As we walk, I’m pleased to find that there’s a wider diversity of shrubs and wildflowers than I anticipated. Some are new to me and others are familiar friends. It’s humid this morning and when the breeze subsides, the midges are upon us in droves; dive-bombing our eyes, buzzing in our ears, and trying to fly down our throats. Losing patience, we don our headnets and continue on, hoping for a light wind.

By early afternoon, we’re at the park, ready for a break. After topping off with water from the surprisingly nice WC, we sit at a picnic table(!) for a relaxing lunch in the sun. We’ve put in 20 miles, but the day is still young and we’re excited for what’s next. We press on, knowing that camping is only allowed in designated sites within the park, and our next chance will be in 12 miles.

The sound of a roaring river beckons us to the edge of a gaping canyon. A hundred feet below, we see a wide, rushing, milky torrent making its way to the sea. Jökulsá is the second longest river in Iceland. Its source is the Vatnajökull glacier, which we will spend the next seven days walking towards. The canyon, we learn, was carved 8,000 years ago from a lava blockage in the water course which caused catastrophic flooding. Its walls consist of ornate columnar volcanic rock, indicating that the lava cooled slowly.

Enlivened by the change in scenery, we dip in and out of treed patches, admiring the river below and the plethora of little waterfalls gushing from the canyon walls. As the miles stretch on, our bodies feel the impact of the miles on our feet coupled with the weight of our packs. Breaks become more frequent and our pace slows. After what feels like a long afternoon, shadows already long and air cool, we close in on Dettifoss. We’re pleased to find camp in a circle of large, wind-protected boulders. We’re even more pleased that the park has cached water here for hikers, saving us a trip to find it. Bodies aching, we’re grateful to be done for the day.

I wake up refreshed and with childlike excitement for the day ahead. “Today we see Dettifoss,” I whisper to Troy. Dettifoss is one of the most powerful waterfalls in Europe and a landmark I’d been looking forward to since I started planning. The sky is grey today and there’s a cool breeze, but it doesn’t feel like there’s precip coming. I sling my pack on and notice it finally feels just a tiny bit lighter; a good feeling. After an obligatory visit to the heated park bathrooms (very nice!), we follow a short path to the canyon’s edge.

Being early, we have the rare treat of experiencing this famous feature with no one else around. Thousands of gallons of water plummet over the cliff, vanishing into the churning, self-created spray and roar below. Along the banks, thick carpets of vibrant moss peppered with tiny white flowers blanket the ground. Exposed soil indicates where whole slabs of peat have slid into the abyss.

Droplets from the spray cloud gather on our coats and the thunder of the water is so loud that we have to raise our voices to speak. So we don’t speak much and instead admire the powerful scene in silence. Like the jumping flames of a fire, it’s mesmerizing and I could watch for hours, but we’ve got places to go. Before heading off into the moonscape toward distant peaks, we walk upriver to Sellfoss, a smaller, though still extremely impressive, waterfall.

Heading west, the gravely ground provides fast, firm travel. We drop over a rise into a rolling health-willow-dwarf birch valley. Hints of crimson ground cover and yellow willow leaves draw my attention. It’s early August and fall is already here. I spot four fuzzy mounds — more sheep! I’m amazed by how the sheep can live here in the harsh conditions, with seemingly little water.

We’re aiming towards a mapped hut, hoping it will provide a cozy spot for lunch. What we find is a dilapidated, mouse-infested shack. We sit behind the building for a break from the wind. Clouds build over the afternoon as we make our way towards Krafla, one of Iceland’s most active volcanoes. Sprinkles begin and soon it’s a full on downpour. I’m warm enough, as long as we keep moving.

Sheets of rain over the moonscape feel ethereal, other-worldly. Pushing forward into the drizzle, engaged by the navigation and scenery, I look up to find that we’ve entered a valley bordered by ochre cliffs. The rain has ceased and it smells of sulfur. Reindeer and snow lichen cover the ground, reminding me of the Brooks Range. Silently, a Golden Plover takes flight from behind a rock. We crest a small pass, collect water from a stream, and make camp on the leeward side of a knoll.

Wind howls and rain pelts the tent throughout the night. When it’s time to get up, it’s cold, blustery, and misty. I very much do not want to get out of my quilt and start walking in the windy drizzle. But, we need to keep moving and also, today is the day we get to Reykjahlíð, a small village where we can get a good meal and top off our food supply. We don rain suits and get going.

Iceland’s geothermal activity is driven by a hotspot that sits atop the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which roughly splits the country in two along a north-south axis. The Ridge forms the divergent boundary between the North American and Eurasian Plates and along it are many of Iceland’s most active volcanoes.

This morning, we’re hiking over the shoulder of one of these volcanoes, Krafla, which last erupted in 1984. Viti, Krafla’s crater, is about 1,000 feet in diameter and 150 feet deep, and contains a striking blue-green lake. At the crater’s edge, we stand in the rain gazing down into the aquamarine pool. Beyond the crater rises billowing steam from the Krafla Geothermal Station, which drives two large turbines.

Departing Viti, we enter an extensive lava field that will take us the remainder of the way to town. Thankfully there’s a path as it’d be nearly impossible to navigate our way through the mangled landscape otherwise. Even with the path, it’s tough walking across sharp, rolling ridges of pumice. Fumaroles spout steam from russet hillsides. I’m making connections between what I saw on satellite imagery months ago with what it’s like to actually walk here.

By mid-morning we’re in Reykjahlíð, setting up camp with front row views of the massive Lake Mývatn. We enjoy the amenities including a hot shower, covered cooking tent, indoor bathrooms, WiFi, and outlets. The small village has everything we need, including a couple of restaurants and a small grocery to top off our supplies. Chores complete, we focus on resting. Our next stop is Landmannalaugar in eight days.

I drift off thinking how good it feels to finally be getting into the rhythm of the hike. There’s a liberating simplicity in knowing that our daily life for the next ten days is walking, eating, and observing. Just be present to the experience and the surrounding landscape. I hope that we stay healthy and that the Icelandic weather is kind to us, or at least not too punishing.

Reykjahlíð to Landmannalaugar

I’m grateful for a refreshing stay and ready to move on. In the morning mist, we trace the eastern edge of Myvatn heading southbound. Mist becomes a light drizzle. At least it’s relatively warm and not windy. The landscape is lagoon-like with little lakes, grassy pumice islands, and ducks sitting peacefully atop still water.

With the straightforward navigation of this section, there’s plenty of time to let one’s mind wander. I think about how much trail and road walking we have on this route and question my decision to come here, knowing my love for the engaging nature of an off-trail route. But, there’s something that this type of walking offers that off-trail hiking does not: space for your mind to relax and go where it needs to go, thoughts untangling with each footstep forward.

I think about how this trip is a 40th birthday present to myself. I think about how I’m grateful that my body can still put down high mileage days. I think about the length of a life, about the passage of time, about my dad’s death and my mom’s health.

After nine miles of misty, midgy shoreline walking, we break off to the south, entering pastoral sheep land. Grass fades to broken rocks and soon we’re back on the moonscape walking towards Sellandafjall, a large mountain on the horizon. With no trees to provide scale, it’s hard to gauge distance here. We walk towards it for hours. We break, we lunch, we talk, and we walk in our own thoughts.

I remember on the Oregon Desert Trail walking towards a lone tree on the horizon for much of the day, miles upon miles of the same sage-specked landscape flowing by. Then suddenly you’re at the tree, emerging from a time warp, unsure of how many hours have passed. And it almost doesn’t seem real; this thing you’ve been walking towards all day. Then the process unfolds in reverse as the tree slowly fades into the distance behind you. It’s refreshing to step out of the time-space continuum of normal life, to slow time down, to just walk and exist; to think of everything, or nothing at all.

An unexpected oasis of green grass and gushing creek appear at the base of Sellandafjall, in the middle of this barren rockscape. A mama sheep and two lambs dart out from their wind-protected den in the hedges. The mama, udder bloated with milk, is limping. Tromping through the heath, we give them a wide berth.

Walking around the base of the mountain takes several hours. Storm cells come and go; rain gear on, off, on, off. Hours later, ducking into a small divot in the land, we pitch next to a burbling stream, using rocks to stabilize our shelter against the wind. It feels desolate and remote here, like we’re on a different planet. I feel my whole body exhale. This is what I was seeking; the emptiness. I fall asleep thinking about the sheep with the injured leg.

At 4:30, I crawl out of the tent to relieve myself and the entire expansive sky is streaks of pink, blue, and mauve. A blazing golden sun crests the eastern horizon. I watch it until I’m too chilled to stay out any longer.

Endless gravel roads carry us towards the Dyngjufjalladalur valley as moody skies loom above. The moonscape turns briefly to green sheep pasture near an unnamed river that marks our turn. Continuing deeper into the Highlands, any remaining greenness soon fades to lava rock and desolation. We won’t see the sheep again until we’re at the southern coast.

Mid-morning, Botni hut provides a pleasant break from the wind. It’s howling today. I make tea and wish we could stay the night, but we have 14 more miles to our intended destination. A sign posted to the door states that our next water source may be dry. We don’t know how old the sign is, so we grab a little extra, but with already heavy packs, we roll the dice and hope the upcoming creek is flowing.

Exiting the hut, the wind has picked up and the mountains we’re hiking towards become veiled behind what at first looks like sheets of precipitation, but which turns out to be a cloud of sand. Entering the valley, the landscape funnels the wind, which is now gusting at 35-40 miles per hour.

I lean into the wind—a solid, invisible wall—forcing my body forward, toward the valley head. It takes the full weight of my body just to maintain balance. Next to me, I see Troy’s silhouette fighting the same impossible force, bracing against the whipping dust. The sky is gone, replaced by a churning, opaque fog of beige dust. Every inch of me is covered, yet the sand finds a way in. Beneath my buff, grit scours my teeth, and my eyes, burning behind sunglasses, water incessantly. All I hear is the constant rattle of thousands of grains of dust blasting the hood of my jacket. Two questions swirl in my head: What am I doing here? Why did I feel compelled to come here?

After a distance that felt much longer than it actually was, we’re at the Dyngjufell hut. We hadn’t planned to stay here, but it’s hard to justify hiking on in these conditions. Inside the vestibule, I force the door closed against the wind, stunned. It’s such a relief to be out of the sandstorm. On top of that, the water source, a small ephemeral snowmelt-fed stream, is flowing.

The hut is managed by Akureyri Touring Association of Iceland. The huts are not as common here as they are farther south, but several can be found scattered throughout the interior. Beds can be reserved in advance, and remaining spots are first come, first serve. Fortunately, no one else was here. At $50 per person per night, it’s not inexpensive, but when you need it, they provide refuge in a very barren, harsh, and remote volcanic landscape.

The interior is clean and simple, providing all that the weary traveler could ask for. A kerosene stove for heating, chairs, a folding table, bunk-style beds, a propane stove for cooking, kitchen ware, and I count, 25 brightly colored mugs. We talk briefly about the prospect of hiking on a bit, but the suggestion feels foolish when we, quite fortuitously, have this incredible place to sleep tonight.

Grateful to be inside as the gusts sway the structure and sand hammers the window, I can’t imagine trying to pitch a tent in this. An inreach forecast suggests that the wind will continue for the next two days, but that this is the worst of it. I stare out the window, content to be exactly where I am, with no internet access or chores to do or anything to distract. Just here. Now.

By dawn, the wind has relented to a steady 20 miles per hour, the sun is shining through and I see the surrounding mountains which were concealed behind dust yesterday. Just as our packs have gotten noticeably lighter, we load up with four liters of water for an all-day dry stretch. Just like every day on the Sangres Traverse. It’s particularly silty here. We didn’t bring alum but we’ll let it settle and decant off the top.

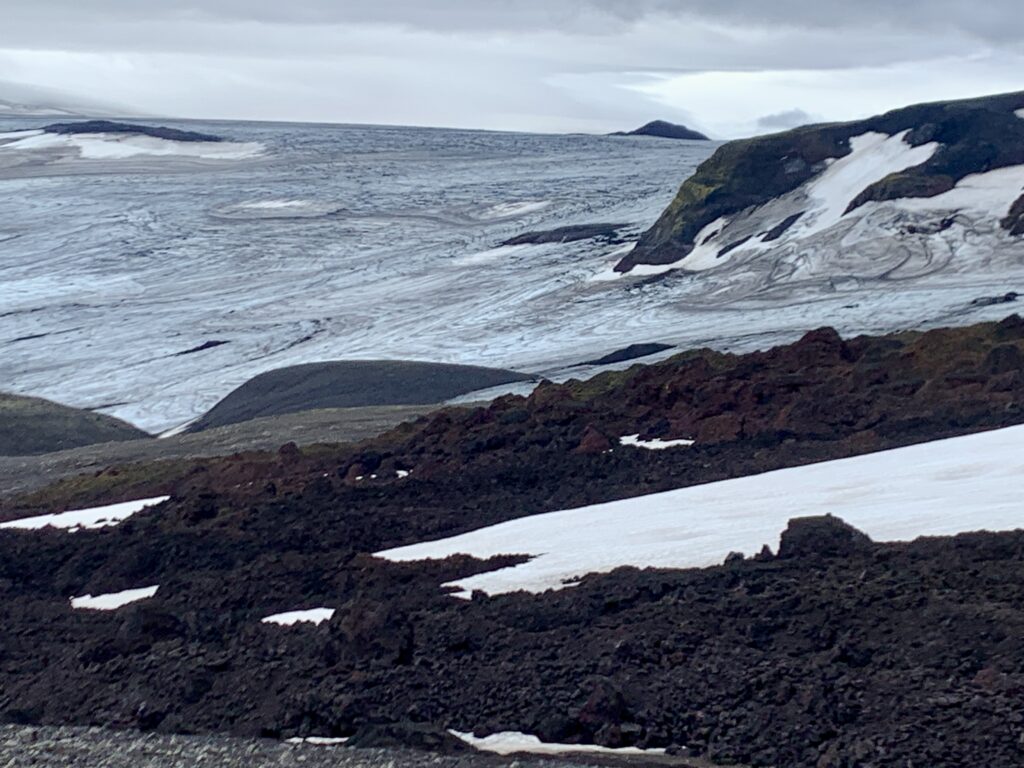

We continue our slow ascent towards the center of the island. Cresting the valley head, I see a massive cloud covering the entire horizon. I stare, trying to make connections in my brain, and realize I’m looking at the Vatnajökull ice cap. Covering eight percent of Iceland, it’s the largest ice cap in Europe, and the source of the river we first encountered on day two. Spindrift creates a snowy mirage above the surface and, as we cut west away from the ice sheet, I wonder what it would be like to walk along its edge, and regret that we didn’t plan our route that way.

With the exception of a few protected spots, the terrain is wide open and the wind is relentless today. The incessant noise is exhausting. Fortunately, the sky is clear and it’s sunny and warm. Vatnajökull remains a steady presence on the horizon, capturing our attention as the hours pass.

Still gusting when we reach our planned camp, the wind is coming from every direction, and despite our best efforts, there’s nowhere less blustery to set up. We select a large boulder and build a two foot tall rock wall around the sides of our tent. Even with our tent battened down as securely as possible, the DCF flaps incessantly. We crawl in, exhausted from fighting the wind all day, hoping our body weight will help stabilize the tent (it doesn’t). We unpack and soon there’s a fine black dust covering our quilts, food bags, and everything else. I clumsily prop up my trash compactor bag and empty backpack to cover the mesh. It’s marginally effective.

With earplugs and an eye mask, I manage to get at least some sleep despite the wap wap wapping of the shelter walls. Everytime I wake up, the wind is still at it. I bury my head back under my quilt. After much tossing and turning, I peak my eye out from under my eye mask and see light. Emerging from my cocoon, I assess the scene. Our bodies and all of our items have several millimeters of black sand atop them. The wind is still battering the tent. Ugh.

Feeling tired and defeated, we pack up, wrangling our tent into a ball, grit spraying in our eyes and mouth. Today is just a day of walking. For most efficient travel, we follow F roads, rough, unmaintained 4×4 tracks that create passage across the rugged interior. The wind continues. I have no poetic thoughts. I mentally count the miles to our next snack break, to water, to lunch. My mind needs more stimulation. I challenge myself to find the highlights: we’re getting closer to Vatnajökull, I see some River Beauties by a stream, we pass an unexpected waterfall, and my body feels strong. As I drift off to sleep, I’m buoyed by tomorrow’s forecast: dense fog, but no wind or precip!

Awake before my alarm, I notice how silent it is. It’s a silence I’m not used to. No birdsong, burbling creek, or wind. A total absence of sound. A low fog covers the valley. We’re walking in a dreamscape, slowly ascending. Cresting the watershed divide for northern and southern Iceland, the ceiling lifts enough to give us incredible views of Vatnajökull. We’re close enough now to see the many nuntaks, outlet glaciers, and textures of the ice.

Dropping into a wide valley carpeted in lime green moss and criss-crossed by slow flowing river braids, I take in the rhyolite mountains with clouds draped over their peaks. It’s spectacular. Again, I notice the silence. With no megafauna, and very little human or air traffic, it feels liminal, like a forgotten wing of a museum that’s been closed to the public for decades.

Crossing a steaming river, we skirt the valley where the footing is firmest, following yellow-capped posts. It begins to drizzle again as we crest a small pass from one valley to the next. The last hours of the day are spent walking the shores of the massive Hágöngulón reservoir. Today was my favorite day so far.

I awake the following morning to a dense fog, which finally burns off by mid-morning shortly after we intersect one of the main F-roads. I’m not psyched to be walking a road (even if it’s dirt) and I question whether I should be spending this time doing something else, like an alpine high route. It’s interesting, this recurring theme of questioning my decision to come here. But I don’t regret coming. It’s been a good experience for Troy and I. And the beautiful parts are outstandingly beautiful. And mostly, it’s the silence and the emptiness that I’ve really loved. I realize that’s what I was hoping to find here, and I did.

For the first time on the trip, the weather is nice enough when we set up camp that I can rinse myself in a nearby creek. It’s breath-takingly brisk and I savor the warmth of the weak autumn sun as I dry off afterwards.

The following day, miles pass quickly on the F-road and we’re rewarded with incredible 360 views of glaciers, mountains, and lakes. Traffic, unfortunately, picks up the farther south we go. We have to keep walking longer than we want to find a decent camp, but we finally come across a great little nook by the Tungnaá, an intimidating river that flows from the western edge of Vatnajökull.

In the morning, we walk the final miles to Landmannalagur, aka the Promised Land. We’re walking through a lush, mossy green dreamscape and spirits are high. Thousands of viridescent veins weave through bands of obsidian rock on the mountainsides. We skirt the edge of a lake-filled crater with rhyolite cliffs. Finally, we’re walking in the mountains, not just near them!

Landmannalaugar to Skógar

Landmannalaugar, though a bit jarring due to the hoards of people, does not disappoint. We soon find ourselves at an adorable converted school bus that houses a small snack and camp supply store. There are no price tags. I’m pleasantly surprised by the variety of items they stock, from a plethora of camp food to bath towels and personal care items. I look for hydrocortisone cream to soothe the itchy blisters that developed on my knuckles a few days ago. Alas, there is none. I shrug and figure I’ll deal with it in a few days when we’re done.

Nearby signs inform me that Landmannalaugar translates to the People’s Pools and has been a rest stop for Icelanders for centuries. Historically, it was used as a place for sheep herders to rest after rounding up sheep in the Highlands. Currently, it serves as a tourist stop on the Ring Road and launching off point for Lagavegur trail hikers.

Unable to resist hot food that we don’t have to prepare on our camp stoves, Troy orders a grilled sandwich and I get a bowl of chicken soup. We add a bag of Lay’s, avocado dip, and two hot coffees. Basking in the heat of the kitchen bus, we eat with the intensity of starved dogs. It’s wonderful to feel full.

Next up is a soak in the natural hot springs. Steaming water pours from the cliff face into wide streams lined with tall grass. Stepping in, the water is so hot that I can’t stand it for more than ten seconds. I yank my foot back and try again farther downstream where the water has had time to cool. That’s better. I ease in and submerge my body. It feels glorious to get the grime off and allow the heat to soothe my muscles. Blessed with an uncharacteristically warm and sunny Icelandic afternoon, we crawl out and dry our bodies in the sun.

Warmed and relaxed, we return to the bus for more treats, savoring the amenities and opportunity for R&R before the push of the final two days. It’s hard to believe we’re finally here. The last two weeks have simultaneously gone both slow and fast. Long days, fast weeks. We’re eager for this next section, the famous Lagavegur and Fimmvodehauls trails. Be present, I remind myself, enjoy this last bit.

I sleep poorly in the crowded campground so we’re up and on trail early. Fortunately, no one else here gets up early so we have this otherwise popular trail to ourselves for the first several hours of the day. Climbing out of Landmannalaugar into the surrounding mountains, the hot springs shimmer in the morning light, billows of steam rising into the air. Geothermal features abound: fumaroles, boiling mudpots, open vents spitting steam, and multicolored mineral-coated rocks. I snap one photo after another, trying to take it all in.

The higher we climb, the more the wind picks up and soon we’re walking inside of a cloud. It’s very blustery and very cold. Well-placed cairns carry us to the Hrafntinnusker Hut, where we find temporary escape from the wind huddled behind the wall of the structure. We eat a quick snack, down some water, and carry on.

Despite wearing every layer I am carrying, I am deeply chilled; the coldest I’ve been on the entire trip. Still pushing through the fog, a light drizzle begins. I am walking as fast as I can, trying to generate body heat. I’m again taken aback by how quickly the weather can change from the pleasant heat of the morning to the frigid wind and rain we’re now walking through. Nonetheless, I think, the surrounding landscape beneath the cloud layer is still beautiful.

Dropping elevation, the fog thins as we walk below the Kaldaklofsjokull glacier and look south over the valley containing the Alftavatn lake and hut. We descend through beige, salmon, and rust colored peaks streaked with black obsidian, fluorescent moss, and crystalline ice. By the time we reach the hut, we’ve warmed enough to shed layers. Tucked out of the wind, we lunch on dates, peanut butter, and coffee.

Onward into the green wonderland, time passes imperceptibly amidst the engaging terrain. After miles upon miles of rolling roads over the past week, my body relishes the dynamic movement, the climbs and descents, the endless single-track carrying me from one beautiful valley to the next. For as well-traveled as it is, I am surprised by how rugged parts of the trail are: steep embankments, washed out drainages, ice crossings, and eroded slopes. In the afternoon, we ford the Blafjallakvisi, which is just over knee deep, but not flowing too quickly.

Our camp, near the Emstrur Hut, is perched in a lush little ravine, roughly two miles from the toe of a glacier that pours into the valley. Cozy in our tent, with blue skies overhead, we make tea and enjoy the satisfaction of a solid day. We finish tomorrow!

Sluggish with the cumulative fatigue of the past days and weeks, we roll out of camp with the knowingness that this is the last time we need to do this for the foreseeable future. The sky is clear and for the first time in a while, I am hiking in just my sun hoody as we cross the narrow gorge of the Fremri-Emstrua on a precarious bridge.

I feel the sharp rise in heat and humidity the lower we drop and the closer we get to Þórsmörk, the terminus of the Laugavegur. Before reaching the small village, we ford the Þröngá. It consists of several knee-deep braids, and is faster flowing than the other rivers we’ve encountered. Safely on the far bank, we enter a national forest composed of birch trees. I haven’t seen trees since we left the northern coast, and it feels wonderful to walk beneath the canopy. I notice gold and crimson tinting the leave’s edges. Fall comes early to the (sub) arctic.

Þórsmörk consists of a few bunkhouses, a campground, a WC, and a small store. As a popular tourist stop and terminus of the Lagavegur, there are many people coming and going. WIth another sixteen miles and 3200’ of elevation gain ahead of us on the Fimmvörðuháls trail, we have a quick coffee and protein bar and push on. The Fimmvörðuháls climbs up out of Þórsmörk, passes between the Eyjafjallajökull and Mýrdalsjökull glaciers, and then descends to Skógafoss waterfall on the southern coast, where we’ll end our journey.

We walk the spine of a verdant ridge, water gushing from nearby waterfalls and through the valley below. Clouds thicken and as we climb higher, strong wind drives rain into our faces. The higher we go, the harder it blows. I worry about the next few hours of the hike as we’ll have to go farther up before we can go back down. Pressing on, we top out in a lava field between the two massive glaciers, famished from the climb and the cold. I remember to look up and I am awed by the textures and swirls in the ice, so close I can nearly touch it.

We eat a quick lunch in the sheltered lee of a giant caldera—a barren, black expanse that feels like the moon—before continuing on through a snow field and over a rise, where we catch our first glimpse of the southern coast and the gray ocean beyond. After two weeks focused only on the next step, seeing the horizon—the literal end—felt like a physical release of tension. Working our way through muddy rivulets across the toe of a glacier, we slip and slide on the ice. Adrenaline all but shot for the day, the final eight miles are slow as we descend towards the sea.

Intersecting the Skógá river, we hike along its bank, passing one waterfall after another through a whimsical valley. Crowds thicken as we close in on Skogar, our endpoint and a popular destination on the Ring Road. It’s obvious why all these people come here, of course – it’s extraordinary. It’s also a stark contrast to the paucity of people we’ve seen over the previous twelve days. I am glad we experienced Iceland the way we did; by crossing the country on foot and confronting its less-traveled interior. It felt like we earned a raw, honest taste of this magnificent, unforgiving island.

We treat ourselves to Kristalls from the camp store and set up our tent near the river, hoping to drown out the tourist noise. Tomorrow we catch the bus back to Reykjavik. Shortly after we tuck-in for the night, it begins to rain hard. It lasts all night and into the next day. I think about how lucky we were with the weather; how good it feels to not have to walk in this today.

As the bus pulled away from the coast the next morning, the rain was still falling. We were trading the vastness of the Highlands for the crowds of Reykjavik. Yet, I didn’t feel a need to rush back to the noise. The two-week crossing, with all its beautiful stillness and brutal wind, had served its purpose. I had found the vastness and simplicity I’d unknowingly sought. I was grounded by a deep appreciation for the quiet, difficult spaces in life—both on the map and within the mind. The journey is over, but the wide-open expanse of Iceland remains, and the stillness I found there comes home with me.