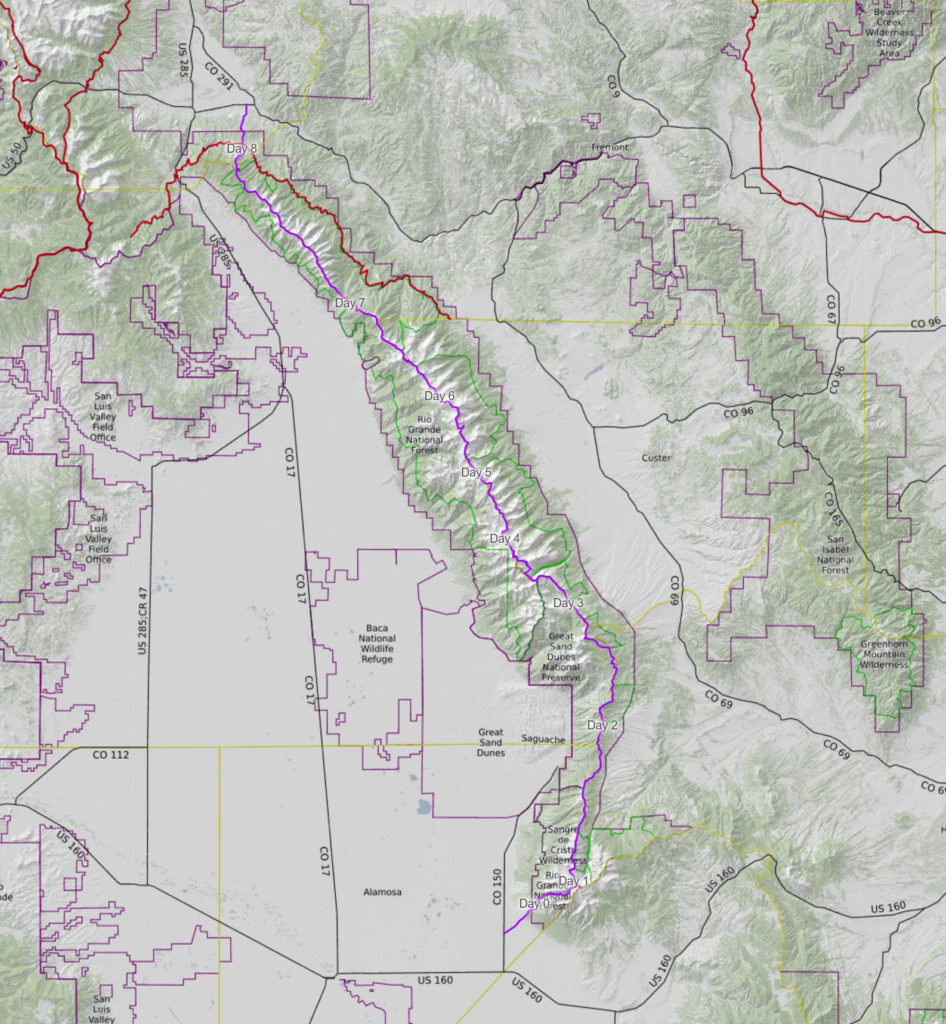

In August of 2023, I hiked the ridgeline of the Sangre de Cristo mountains from Blanca Peak to Methodist Mountain. This is referred to as the Sangre de Cristo Traverse.

Though there are variations on the route, the primary Sangres Traverse runs along the central spine of the Northern Sangre de Cristo range, a subrange of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. The main ridgeline traverses over 77 peaks, including five fourteeners and two thirteener centennials. It contains sections of extended class 3 hiking as well as class 4 and low fifth class scrambling. Depending on various factors, such as the weather or one’s comfort on technical terrain, alterations to the primary route can be made.

This post provides an overview of the route as well as highlights from each day and the trip as a whole. It’s intended to be informative rather than instructional. Linked below are my gear list and food planning spreadsheet. If you don’t like reading, scroll to the bottom for 21 of my favorite photos from the trip.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse Overview

The route I completed covered 115 miles and 55,000 feet of vertical gain. These numbers include dropping off the primary ridge into basins for camp, water, and weather/technical detours. I was joined by Troy Klaassen and it took us 8 days to complete the route. We carried all of our food and gear from the start.

From Blanca Peak to Methodist Mountain, we followed less than 10 miles of established trail/road; instead hiking cross country and utilizing elk and sheep trails when we were lucky enough to find them. The majority of the travel occurred above treeline (~12,000’) where we were exposed to howling winds, intense sun, and rocky scrambles. Due to being on top of a ridge, there were no “on route” water sources and few opportunities to take cover if/when weather suddenly rolled in.

My goals going into this trip were to:

> Explore the Sangres on foot with the intention of developing a more intimate knowledge of and connection to the place I live

> Stretch and enhance my physical and mental capabilities (e.g. daily vertical accumulation, off-trail navigation and route finding, adaptability to rapidly changing circumstances, etc.)

> Connect a line on foot from the Highway 150/Lake Como Road intersection to Highway 50/CR 107 in Salida while staying true to the range’s central ridge as much as feasible

In preparation for completing this route, there were several resources that I found helpful and/or inspiring. These include Justin Simoni’s 2019 (south to north) and 2023 (north to south) trips, Hannah Green’s 2022 FKT, Nick Clark and Cam Cross’s 2018 FKT, and Brendon Leonard and Jim Harris’s 2013 backpack from Methodist to California. Additionally, a couple of long distance hikers I know, Cam “Swami” Honan and Alex “Pepperflake” McNaughton, have completed high route/traverses (separately) between Blanca and Methodist. From my understanding, the first attempt to traverse the range was by Bill Arnold, and Lester and Jim Michel in 1961 when they hiked from Poncha Pass to Music Pass.

Highlights & Takeaways

The entire trip was a highlight and as with any adventure, there were takeaways to be gleaned, but as I reflected on the trip in the weeks afterwards, there were a few themes that stood out.

The value of relationship to place. In researching and walking this route, I became infinitely more familiar with this range that I’ve lived by and recreated in for years. It felt special to connect many of my favorite local spots in one trip and to see from a new vantage point the peaks that I literally look at every day on my morning walk. That said, more than leaving me with a feeling of “been there, done that,” this trip revealed to me how much more there is to explore: so many subsidiary ridges, treed valleys, and alpine lakes.

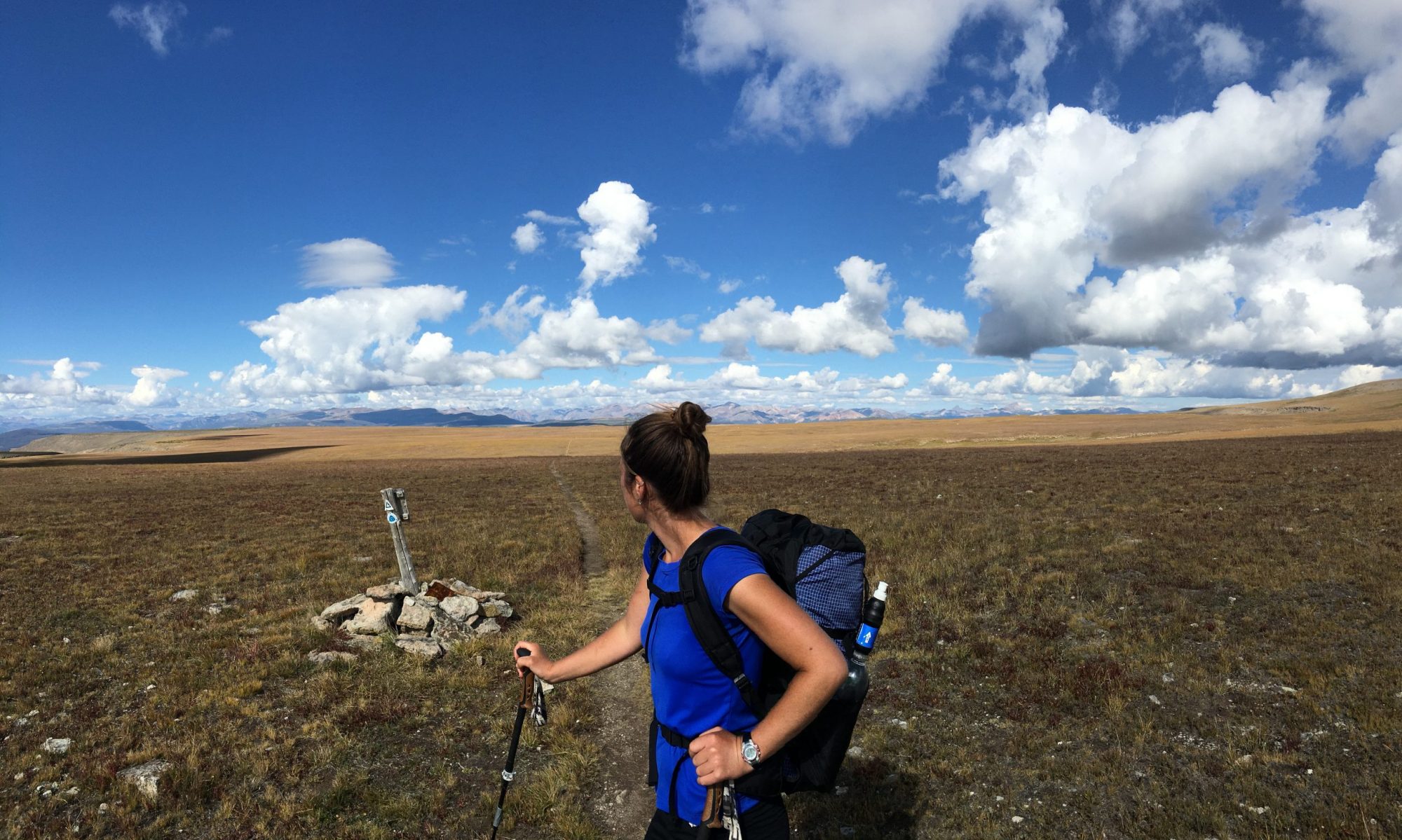

The diversity of the terrain and the natural beauty. Following one ridgeline probably sounds boring to a lot of people, but I found it endlessly enjoyable. I was surprised by the diversity in terrain from the technical class 4-5 sections of the Blanca and Crestone massifs to the many steep class 3 thirteeners that pepper the ridge, to the rolling tundra found farther north. The unique positioning of this range with the massive San Luis Valley (SLV) to the west and the Wet Mountain Valley to the east, and the ability to stare down the ridgeline to our farthest objective was awesome. The remote alpine basins and hidden tarns, the colorful sunrises, and the dramatic clouds that flowed over the ridge never got old.

The importance of a good partner. These types of trips (off-trail, remote, demanding, multi-day) are physically and mentally taxing, to put it lightly. You need to be out there with someone you trust, whose risk tolerance is similar to yours, whose fitness is on par with yours, and with whom you can communicate openly. Ideally, you’ve already been on many shorter outings with that person, you’ve vetted each other, and you know it works. When you’re out with a trusted partner, that can make the trip all the much better. The opposite is also true. This is a tenet I was already well aware of from my Great Basin hike and Grand Canyon Traverse with Ryan “Dirtmonger” Sylva. This trip reinforced the value of a good partner to me and spurred self reflection in both what I seek in a hiking partner as well as the ways I can be a better one to others. Our team work wasn’t perfect, but I’m appreciative to Troy for the ways he showed up as a solid partner during this trip and in the debrief afterwards.

Gear List

Find my complete gear list here.

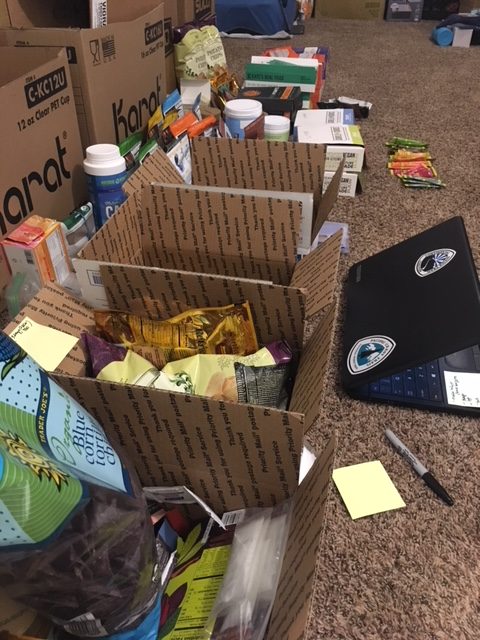

Nutrition & Food Planning

Read about my food planning and nutrition here.

Day by Day

Day Zero

Around 1pm, we leave Troy’s truck at the dirt lot that marks the junction of Lake Como Road and Highway 150. It’s finally time to start this thing.

I’m a bundle of nerves and excitement.

I’ve been considering walking this range for years. It’s hard not to when you drive highway 17 through the San Luis Valley. The picturesque north-south ridgeline begs the question: could I traverse that whole thing on foot from end to end?

This range inhabits a special place in my heart and mind. I’ve lived on the north and south ends of the range, fallen in love on its flanks, had my heart broken here, buried my late cat under a Pinyon here, built lifelong friendships here, completed my 14ers here, and driven around these peaks more times than I can count. If there’s any place that’s felt like home in my adult life, it’s these mountains.

It’s 85 degrees on the hot, exposed, dusty 4wd road that we must walk up to access the main spine of the ridge. Our packs are heavy with 8 days of food and a few liters of water. We’re both feeling a little nauseous from the heat and exertion. I also drank too much coffee this morning which isn’t helping matters. We rest in the shade of Pinyons, slowly making our way up the 4400 vertical feet towards our camp near the base of Blanca.

Golden aspen leaves on the trail tell me that the transition to fall has already begun in the high country. We hike past Lake Como and find a higher camp near Blue Lakes at 12,200’. The day’s heat subsides as we gather water, cook dinner, and discuss tomorrow’s plan. The basin’s three 14,000’ peaks (Little Bear, Blanca, and Ellingwood Point) loom above, tinged with alpenglow.

I go to sleep grateful to be out here after years of dreaming and months of planning. As with the start of any real adventure, I know challenging times are in store, but I don’t know exactly when they’ll arise and what form they’ll take.

Tomorrow the real work begins.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse Day 1

At 5:03 my alarm sounds and by 5:11, I’m drinking coffee in the dark, watching the stars fade as dawn lights up the edges of the sky.

By 6, we’re slogging up towards the Blanca-Ellingwood ridgeline To the west, the shadow of the Sangres is taking form on the floor of the expansive SLV. At the top of Blanca, we high five, “one down, seventy plus to go” I say.

Being that it’s a Saturday, there are several other parties on the mountain, but after departing Ellingwood Point on the class 3 and 4 ridgeline over to California Peak, we don’t see another person until the end of the following day when we drop into the Great Sand Dunes Preserve for water. The weight of the full backpack makes the ridgeline scramble feel much more challenging than it did on a scouting mission 2 months ago.

We drop north off California and the whole range – the entire following week’s work – is laid out in front of us. The crest drops away to the SLV in the west and the Wet Mountain Valley to the east. We walk rolling tundra for the remainder of the day and make camp in a protected area ~12,200’ behind a knoll south of Carbonate Mountain.

I walk up to the ridge to pee before getting into my tent and I’m astounded by the beauty of the scene that greets me on the other side of the ridge: rain showers over the Sand Dunes and valley to the north tinted pink, orange, and yellow by the sunset. I call Troy up and we enjoy the scene before a chilly wind sends us for our sleeping bags.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse Day 2

The morning is an easy, uneventful four miles down the ridgeline to Mosca Pass, the low point of the route at 9,700’. The spring right off the ridge that we were hoping for is dry and we walk the mile down into the Preserve for water. We go to a spot I’ve stopped at with guided trips in the past. As will become our practice, we fill up for the entire day and head back up to the ridge.

The next 10 miles of walking up and over Mount Zwischen is long, dry, and hot. It’s also littered with blowdowns. The view out over the Dunes from the summit is pretty spectacular though. The descent is steep through dense forest on tired feet.

The most joy I find all day is when I pick up bits of elk trail here and there and we can cruise until the path disappears as suddenly as it appeared. At Medano Pass, we descend 500’ into the Preserve to fill up on water behind an established camp from which dogs are barking at us. We hike the 4wd road out of the Preseve and north from the pass until we find a suitable camp underneath the shadow of Herard.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse Day 3

Shortly before 6am, we begin our daily migration back to the ridge. The higher we climb, the windier it gets. As we crest the ridge, the full force of the gales hit, carrying icy wind up from the shadowed valley to the west. We lean sideways into the 40-50 mph eastward winds as we push north over rolling tundra, summiting one small peak after another.

I need more layers, a snack, a break from the wind. I drop off the ridge to the east where it’s nearly windless and it’s 15 degrees warmer. I wipe the snot from the right lens of my sunglasses. We snack, layer up, regain composure and head back into it. We see weather over Blanca to the south as well as the Crestones to the north. Being almost exclusively above treeline, it’s incredible how far we can see around us – all the way back to where we started, and all the way to where we’ll sleep tonight.

By noon, we’re at Music Pass and we trace out the remainder of our route for the day: Marble Mountain, Milwaukee Peak, and the Crestones, beneath which we plan to camp. A steep 1300’ and we’ve regained the ridge. We skirt through the notch by Milwaukee, enjoying an oddly placed mile or so of nice trail that disappears as suddenly as it appeared.

With 8000’ of vertical on our legs already and daylight waning, we opt to take the Cresolita saddle rather than the ridge directly over Broken Hand Peak. I’m disappointed, but it’s the right call. As we descend into South Colony Lakes at dusk, the pikas’ chirping echoes around the basin. At the outlet of the lake, I achily bend over and wash the grime from my face and legs. We find a protected spot in the willows to settle in for the night.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse Day 4

Morning comes too soon and sleep was insufficient as I spent part of the night defending my food bag pillow from the mini bear that was scratching around at the edge of my shelter. That’s soon forgotten, however, as we begin our ascent and I’m entranced by the red glow reflected off the Needle. Soon we’ve regained the primary ridge via a fun class 3 connecting ridge from Humboldt.

Clouds roll up and over a saddle from the west, blotting out the sun as we climb Obstruction. From the summit, through breaks in the clouds, we look down to Willow Lake, a longtime favorite haven, and across the bumpy ridgeline of 13ers that connects to Adams. In a flat below Adams is Mo Lake, a cat-shaped tarn I christened last August the weekend after I said goodbye to my 17-year old cat.

We descend a steep, loose gully skirting below the first two major obstacles of the ridge, which would’ve required hours of technical scrambling, and reascend at the saddle south of Peak 13517. A series of steep, scree-covered slabs and class 4 moves takes us along the remainder of the ridge to Adams. From there, we follow the chunky class 3 ridge to Fluted. The end of the technical difficulties! I’m both relieved (we might actually do this thing!) and sad. The technical parts, while slow, are an engaging puzzle to solve.

The remainder of the day is rolling block field until we pick up a mile or so of trail in a saddle near Comanche and drop down to Venable for camp. The basin is home to dozens of marmots which whistle at me as I pass through their domains on the way to the small lake. Three deer study me as I gather water. A gentle rain starts to fall and I scurry back to my tent. Cooking dinner from the safety and warmth of my tent, a rainbow appears over Westcliffe to the east. I fall asleep listening to Annie Dillard wax poetic about the glory of nature.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse Day 5

After a night mostly spent listening to the flapping of my tent in the wind, I open my eyes and notice it’s lighter than it should be at 5:03am. I’ve slept through my watch alarm and scramble to pack up as Troy is already almost ready to go.

The day is gloriously repetitive, consisting of going up and over several peaks >13,000’. Up 1000’, down 1000’, up 500’, down 500’, up 1300’, down 1300’. Eureka, Hermit, Rito Alto, Peak of the Clouds, Silver Peak, and on and on. The peaks were a nice break from the slower, technical terrain of the previous day, and more steep and engaging than the rolling tundra I expected. It felt wonderful to walk along the ridges I’ve seen so many times from the lakes below. Occasionally we stop on summit to snack and I just sit and stare contently at where we’ve been and where we’re going.

We make camp early at a small lake below Electric Peak. I take my time setting up my shelter and then walk the half mile to gather water. I’m nearly done when I notice movement in the otherwise still tarn. I think it’s insects at first, but the frequency picks up, and I realize it’s rain drops. Covering the water slowly at first, and then more quickly. I rinse my face and legs and scamper to my tent. I hop in just as the squall picks up. I bury myself in my quilt and eat spoonfuls of almond butter and drink lemon chamomile tea while I watch the rainfall outside. I’m warm, dry, and clean in my tent at a remote lake at 12,400’ in my favorite range. It’s hard to imagine any better feeling in this moment.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse Day 6

I awoke to a lone pika call at 4:30am, feeling rested and grateful for a full night’s sleep. We climb out of our basin camp and as we regain the ridgeline to Electric Peak, a red sun lights up the Wet Mountain Valley. The surrounding peaks emit a golden glow. The shadow of the range begins to take shape in the valley to the west. There’s the outline of Electric and our microscopic figures crawling up it.

At the summit, I look north and spot the Chalk Cliffs. HOME! We’re actually almost there. In a way, it feels kind of unbelievable.

There’s an icy wind, which I’ve come to expect each morning when we regain the ridge. I walk with my hands in my pockets and think about hiking this route again, solo, pushing myself as hard as I can. And then I wonder about that desire to run myself ragged, to walk until there’s nothing left, to find transcendence by searching for the limits of the physical.

Today’s terrain is a continuation of the previous day, and as I hike up another steep rocky ridge, I send a genuine prayer to the universe for endless talus covered 13ers. This feeling is like nothing else: heart pounding, breath rhythmic, in out in out, step step step step, thinking like the sheep, allowing my body to take the most obvious line, connecting bits of worn terrain. Some trampled tundra here, flattened scuffed rocks there, a slight opening in the grass.

At Cottonwood Peak, our main route drops below 13,000’ for the first time in 40 miles. The afternoon is hot and humid as we wind down through blowdown hell (though not as hellish as Zwischen) to Hayden Pass. A quarter mile from the pass my pole breaks. For 25 minutes, we search a small piece of ground for the missing spring. No luck, but I’m grateful for Troy’s help in the search as it’s already been a long day and we’re both ready to find water. We hike out to the pass and descend 500’ before we find a trickle big enough to fill our bottles, and then reascend to make camp.

I watch the cumulonimbus build behind the ridge to the south and darken the valley to the east as my dinner cooks. Flash. 1…2…3…BOOM! It’s close. Dinner is done and the show begins. I watch the storm mingle with sunset light as it passes overhead.

I love this outside life.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse Day 7

I wake up excited for our last full day. We follow old trail up Galena in the twilight. Clouds are rolling in over the pass and the entire sky is pink, orange, amber, and yellow as the sunrise light reflects off the clouds. The beauty is unbelievable.

All day, we hike up and down “bumps” on the ridge inside of a cloud. I feel like I’m in a dream, hiking the same 100′ of talus on repeat. Time is standing still. My watch says we’ve been hiking for 4 hours, but I can’t ascertain any progress.

The clouds begin to break a little after noon and we’re above one of my very favorite alpine swimming spots. On a subsidiary ridge, I spot two sheep descending steep talus. It feels so meaningful to connect all these places I love and these peaks I literally look at every morning on my walk, addressing them by name, “good morning Simmons, Hunts, Twin Sisters…”

My body feels strong, even after 50,000’ of vertical gain in a week. Stronger perhaps than when I started. I feel gratitude for my body’s strength and resilience. I know it’s not a given.

I watch the sky vigilantly all day as storms build in every direction around us. Around noon we drop 700’ steeply off the ridge to get water. This is our original planned campsite, but it’s early and we think the weather will hold a bit longer. So we test our luck, fill up, and push on. And the weather (and our luck) does hold for another few hours; long enough for us to get up and over Hunts Peak. At the summit, we’re greeted with a cold wind and a loud clap of thunder. It’s raining in the valley directly to our east and up north over Salida. Time to get down!

I inhale a few spoonfuls of almond butter, nearly clogging my airway, and then we haul down the steep scree slope as the wind picks up and thunder continues to echo nearby. We bail into a basin on the east side of the ridge, where 500’ down we see some trees and a potential flat(ish) spot large enough to fit our tents. Hail starts to fall as we make our way down the slippery wet tundra and scree slope. We configure a couple of clever camp spots and as soon as we’re set up, it begins to rain in earnest.

I sit in my tent drinking warm emergenc, eating the last few ounce of almond butter, listening to the pikas, and watching the clouds swirl around the basin. Salida is 15 miles and 3k’ of vertical away.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse Day 8

When I awake, the predawn air feels damp and chilly. The sun tries to light up the sky, but we remain inside of a dense cloud for much of the morning. We hike northward, only a few minor peaks and two named peaks before our descent into Salida. After a few hours, the sun begins to burn off the top layer of clouds, revealing the most incredible inversion in the valleys on both the east and west side. The ridgeline is an island of land in a sea of clouds.

Through the dense fog, I walk north, feeling the magnetic pull of home so strongly I can’t slow down. I periodically stop and wait until I see Troy’s figure emerge from the fog and then I turn and keep walking. The terrain has mellowed into tundra and block field. We reconvene beneath Simmons Peak, remove some layers, and then ascend together. The clouds have burned off even more now. The sky is blue. Salida is 6200′ below under a blanket of clouds. Methodist, our final peak, is one connecting ridgeline away.

We gingerly crawl down the wet, slippery, lichen-covered rocks and into the blowdown forest that covers the remaining section of ridgeline. The Decker fire came through here in 2019. Amongst the burned out skeleton trees, fireweed and yarrow add splashes of color to the bare ground.

I’m laser focused as I weave in and out of downed trees and baby aspen groves finding elk trails to link together. I round the side of a knoll and spot five elk as they disappear off the other side of the ridge. Thank you for the trails! I stop to snack on raspberries along the way, but never for long. I’ve got places to go.

After what felt like much longer than it should’ve taken, I’m on the final push up up up the steep southwest ridge of Methodist. There was trail we could’ve taken at the last saddle to bypass this climb, but I forgot, and now I’m here and I’m climbing and panting and soaked from pushing through wet brush, and there’s nothing else I’d rather be doing in this moment than doing exactly this.

And suddenly, I’m standing on a road. It’s the service road that connects to the communications towers on the summit. And shortly thereafter, Troy is there too. We have 9 miles of road walking and 4600′ of descent to Highway 50. We tap poles and commend each other on a well executed trip.

I look at my watch, “we should be to the burger place by 1.”

“Sounds amazing,” he responds and we begin our descent off the ridge that has been our home for the last 8 days. We walk out of the sun, down through a layer of fog, and eventually Salida comes into view.

“I’ve walked out of the mountains into a lot of different towns, but never into the one I live in. It feels pretty great,” I say.

Photo Essay

I intended to pick out 5 or 6 of my favorite photos to share, but here we are with 21.

Photo credit for many of these is Troy Klaassen.